In 1829, the Roman Catholic Relief Act resulted in the emancipation of Roman Catholics and Protestant Dissenters. However, the hope that the act would also put an end to Jewish disabilities were dashed when the House of Lords introduced the words ‘On the true faith of a Christian’ into the oath as a prerequisite upon taking public office. The wording left Jews excluded from politics by their faith.1 A campaign for equal rights, which was to last for decades, began.

In 1835, following the Municipal Corporation Act, the city of Rochester, probably the only municipal body in the country, removed the requirement of the clause ‘On the true faith of a Christian’, ultimately paving way for non-Christians to take office. Nine years later, the parliament passed the Act of the Relief of Persons of the Jewish Religion which allowed Jews to participate in local affairs.2 In December 1850, John Lewis Levy, together with John Foord, Stephen Steele and Edwards Robert Coles, was appointed magistrate to the city – the first Jewish magistrate in the country.3

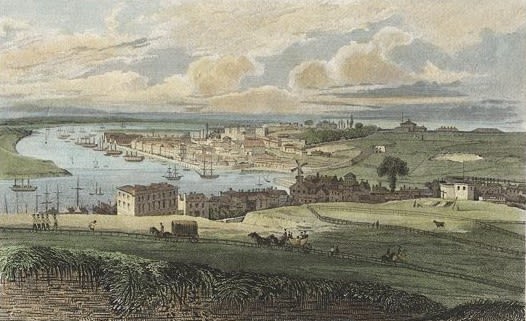

In comparison with Rochester, Chatham was governed by Court Leet – a remnant form of governance from feudal days. It would be Chatham, with its antiquated form of governance, its rather hostile environment, its filthy streets and perpetually drunk soldiers and sailors - described by the historian R.G.Hobbes as ‘the wickedest place in the world’4 - that would prove to be the pioneer of Jewish emancipation in the whole country. On 10 November 1854, following the local elections Charles Isaacs, a Liberal, then in his early thirties, was elected High Constable of the borough for the ensuing year. It was the first instance in England for a Jew to fill a principal office. David Salomons, who until now was thought to be the first Jewish mayor in the country, was elected Lord Mayor of London in 1855.

It was the time of the Crimean war and Chatham was swollen with troops preparing for the campaign or coming back on leave. Local hospitals were full of the wounded and the convalescing. On 6 March 1855 Queen Victoria paid a visit to the town and public hospitals in Chatham and its vicinity and inspected the patients who had recently arrived from the Crimea.

The Queen was hosted by the High Constable Charles Isaacs. At Fort Pitt Hospital, Her Majesty was given a tour by a Jewish surgeon, Dr Jacob Solomon, an alien and a refugee from Cracow, who was left in charge of the hospital, as the army medical staff had been sent to the front line.

In 1856, Chatham’s Court Leet unanimously elected another member of the Chatham Jewish community – John Montagu Marks. During his tenure as high constable, Marks led the opposition to the Admiralty’s decision to reduce the dockyard workers’ pay to 12 shillings a week. He considered the proposed pay to be almost lower than that of soldiers who received 7s 7d per week with fuel and no rent. Marks’s suggestion was to write to other dockyard towns, to induce them to take part in the movement, as Chatham alone would not have an effect on the Lords of the Admiralty.5

In the 1850s the anti-Jewish campaign was rapidly gathering pace. A familiar trope of ‘un-Christianising’ raised its head again, as it did all previous times. If it was acceptable for the laws of a Christian country to be managed by Jews, the country would be in great jeopardy if non-Christians were permitted to be part of the making of the laws.6

A bill ‘for the relief of Her Majesty’s subjects professing the Jewish religion’ passed through both houses of parliament and received Royal Assent only on its fifth attempt, in July 1858.

This article is based on a chapter from Fridman, I. (2020) Foreigners, Aliens, Citizens – Medway and its Jewish community, 1066-1939. Faversham: Birch Leaf. Some of the original references are below. It was published on 30 November 2022.

Bibliography

Fridman, I. (2020) Foreigners, Aliens, Citizens – Medway and its Jewish community, 1066-1939. Faversham: Birch Leaf.

Irina Fridman - Author “Foreigners, Aliens, Citizens” - charting the history of Jewish people in UK

References:

Roth, Cecil (1949) A History of the Jews in England. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, p249. ↩︎

Wolf, Lucien (1898) ‘The Queen’s Jewry – 1837-97’, The Jewish Yearbook 1897-98 (5658), p317. ↩︎

Kentish Independent 23/12/1850 ↩︎

Hobbes, R.G. (1895) Reminiscences and Notes of Seventy years’ Life, Travel and Adventure; Military and Civil; Scientific and Literary. v2; London: Elliot Stock, p103. ↩︎

SE Gazette 10/2/1857. ↩︎

Jewish Chronicle 13/5/1859. ↩︎